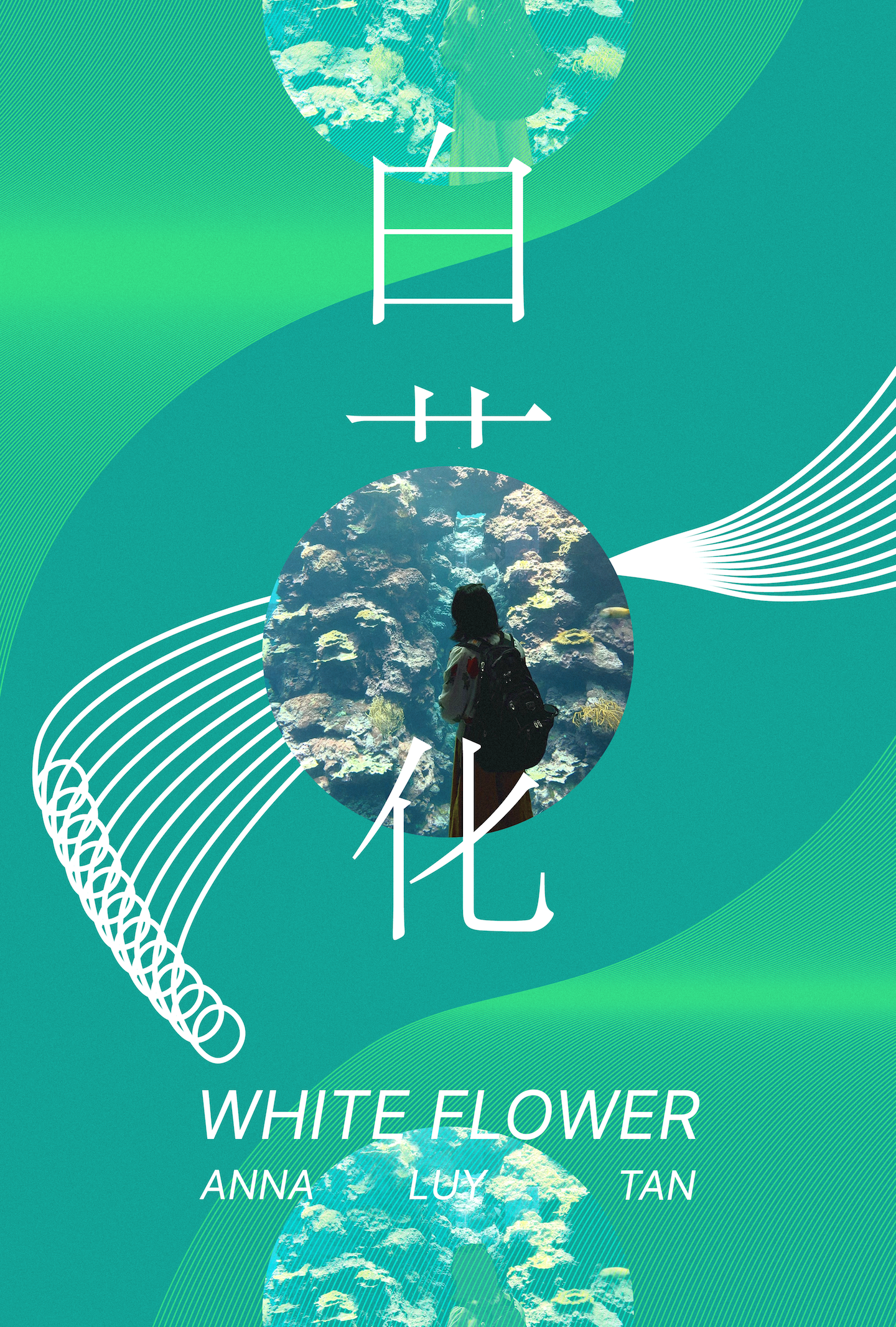

In March 2023, via video call and email, Anna Luy Tan answered questions from PARDICOLOR about her film ‘White Flower’.

Can you tell us about your first experience of the underwater world?

I was utterly enchanted by the underwater world for as long as I can remember. My father is from Davao, in the Philippines and throughout my childhood, we would go there often to visit family. For this reason, I was fortunate enough to be exposed to this world from a very early age. Some of my most cherished childhood memories were of me swimming amongst the most vibrant and biodiverse coral reefs on the planet. Even then, I remember wanting desperately to communicate what I had experienced to the world above. For me, a young girl who grew up in the rural farmlands of the US, this truly was another world, and it never left me. I still regard these formative experiences as the closest thing I’ve felt to a religious experience.

Why did you want to make this film?

When given the opportunity to make this film, I asked myself, amongst all the various topics I am interested in making films about, what is truly the most urgent matter to convey? What film needs to be made right now? Thinking about the incalculable loss and the immense impact the collapse of the coral reef ecosystem would have on our planet and the lives of nearly a billion people is precisely what compelled me to make this film. The fire underneath me that really brought this film to fruition was understanding that the importance of this message lies well beyond me as an individual.

Sir David Attenborough once said that “No one will protect what they don't care about; and no one will care about what they have never experienced”. How important was it to you to share the story of Taiwan’s coral reefs?

I really cannot think of a more important story to share. Our collective survival directly depends on these ecosystems and right now, we are living in a very precious window of time where we can do something about it. The entire point of making the film is for as many people as possible to come into this understanding.

What challenges were faced during underwater filming?

Operating a camera above water is already such a delicate art, let alone doing it underwater where even the slightest current will destabilize you and move the subject out of frame. With all the additional moving factors to consider, underwater filmmaking is an entirely different skill, one that is very much dependent on your ability as a scuba diver and your understanding of the marine environment. Throughout the process of filmmaking, I had to develop a new awareness about the subtle changes and patterns of the ocean itself. It was through the support and generosity of a group of experienced Taiwanese underwater videographers who welcomed me into their community that I was able to learn about this new way of seeing: tracking the tides based on lunar cycles using Chinese calendars, understanding the strength of currents based on the topography of the ocean floor, knowing when certain coastlines would experience typhoons, predicting when the clarity of the water would be highest, or intuiting when and where certain creatures could be seen in their natural habitat. These elders who helped guide me possess an entirely different epistemology of the ocean from that of the scientists, one based on a lifetime of observation, direct experience, and generations of accumulated cultural knowledge. Learning from this community about how to read the ocean and work with its mercurial nature was invaluable and I feel like one of the most personally transformative parts of this project. I could not have done it without them.

Seeing images of bleached coral is distressing, how did it feel to experience such tangible evidence of the effects of climate change?

Genuinely heartbreaking. It is hard to put into words how it feels because what you feel is a loss for the entire world. The scale of this feeling seems incompatible with what humans are normally able to grasp. Our generation will become more familiar with this feeling than any other generation in human history, which is strange to think about. We don’t even have language to fully describe this because it is so unprecedented. What adds to this is that this bleaching is not seen by many people, they are not aware of this accelerated destruction that is right below the water's surface. This seems to only intensify the feeling. When you have seen for yourself the coral reef in full bloom and then the desolation of a bleached area, it really just sharpens your conviction that something needs to be done. There is no reasoning or logic that needs to step in for that to make sense. It’s unavoidable.

Last year Danish multinational power company Ørsted began trialing ‘ReCoral’ in Taiwanese waters, a system designed to grow coral around offshore wind farms. What are your thoughts about this initiative?

After speaking with many different scientists across Taiwan, I have learned alot about the internal politics of coral reef science and the power structures involved. When I approached this subject, I naively thought there would be general consensus from the scientific community, it’s “science” after all! Little did I know coral reef conservation science is a highly contested area of research with widely differing viewpoints, the concept of conservation itself is highly subjective. What I have learned is that you should always check where the money for the research is coming from. If the money is coming from a offshore wind farm company, it would make sense that they will finance research that will produce certain conclusions that will help to justify building more offshore wind farms. This too was a huge lesson that I learned when making this film. Talking with other scientists studying offshore wind farms, they presented me with their findings that show off-shore wind farms disrupt the seabed so that the usual fish populations do not return to those areas. Then again, strengthening our dependency on fossil fuels or anything that emits more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere is certainly not the answer.

What I have gathered about growing more coral is that it is a highly sensitive process that depends on many factors–it is not so easy to streamline. Sometimes emphasizing the potential of coral farms is used to displace emphasis on protecting existing reefs. I think it is best to have an integrated approach where we do not give up on these ancient megastructures that have taken thousands and thousands of years to form while also developing new methods that attempt to foster the growth of new coral, perhaps accelerating the propagation of more temperature resistant strains.

You have recently been working on a film about the Mekong River in Cambodia - are you at liberty to tell us more?

Given the political situation in Cambodia, we are still navigating the ways to safely relay this information so as to not endanger the people involved. But right now I can say that river dredging is massively destructive and is something that we should all educate ourselves on. I think issues concerning water will become some of the most important of our generation, and so I envision the films I create in the future will be centered around this topic.